The Slave Trade Would Continue for 20 More Years

January 2018 marks the 210th anniversary of a major milestone in the history of the United States, and the history of Charleston in particular. On the first day of January, 1808, a new Federal law made it illegal to import captive people from Africa into the United States. This date marks the end—the permanent, legal closure—of the trans-Atlantic slave trade into our country. The practice of slavery continued to be legal in much of the U.S. until 1865, of course, and enslaved people continued to be bought and sold within the Southern states, but in January 1808 the legal flow of new Africans into this country stopped forever.

This change was a major step forward in our nation's long and troubled history with slavery, but it also has particular relevance to Charleston. Why? Because the federal law to close the trans-Atlantic slave trade on January 1st, 1808, was enacted because the state of South Carolina—and South Carolina alone—was gorging itself on the African trade. Our state, and the port city of Charleston in particular, was struggling with an addiction to slavery, and the United States Congress intervened to cut off our supply. In order to understand the significance of the 1808 closure, let's turn back to the beginning of the Carolina colony and briefly review the rise and fall of the business of transporting African captives into the port of Charleston.

The business of importing African captives into South Carolina was not a steady, continuous trade from the planting of the Carolina colony in April of 1670 to the first day of January 1808. Rather, the rate of African arrivals in Charleston evolved over these 137 years, with several peaks and valleys and several periods of interruption. If you'd like to explore this topic on your own, you're welcome to visit the Charleston County Public Library and peruse a wealth of books and articles. If you're interested in crunching the numbers of all of the documented trans-Atlantic slave ships that unloaded in Charleston, you can point your Internet browser to an amazing website called The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, at http://slavevoyages.org.

For the purposes of today's story, however, I'm going to stick to a more general timeline and leave the discussion of numbers of people for a later discussion.

The first enslaved Africans came to South Carolina by way of Barbados, either at the end of 1670 or early 1671. Over the ensuing thirty years, a relatively steady stream of Africans flowed from the English West Indies into the port of Charleston. The total number of enslaved people brought into South Carolina was rather small during these early decades, however, for a variety of reasons. First, we were a fledgling colony, and so it took years to build up trade networks and plantation infrastructure. Secondly, the Royal African Company, chartered in 1660, held a monopoly on the English slave trade until 1689, and then a virtual monopoly until 1698, when Parliament passed a law that opened the business to any English merchant.

Between 1699 and 1719, the English slave trade definitely increased, but the number of Africans arriving in Charleston was still not great. The most important change was the source of the enslaved people coming to South Carolina. In the early 1700s, ships began arriving here directly from the west coast of Africa, not just from Barbados, Jamaica, or Antigua. By the year 1708, the number of enslaved people in South Carolina exceeded the number of white Europeans. To put it another way, by 1708, it was clear that the planters of South Carolina, like their contemporaries in the West Indies and in South America, had become addicted to the profits generated by the exploitation of their fellow humans.

Following a bloodless coup, or revolution, in Charleston in December 1719, the political and economic future of South Carolina seemed unclear. In many ways, the colony was struggling for survival throughout the 1720s. Only a small number of white Europeans emigrated to South Carolina during these years and the economy stagnated, but the African trade to the port of Charleston continued along at relatively modest rate. In the summer of 1729, after nearly ten years of negotiations, the Lords Proprietors of the Carolina colonies sold the entire enterprise to King George II. This change from Proprietary colony to Royal colony was like a green light to immigrants, potential investors, and political schemers. South Carolina was now well-poised for expansion.

The first decade of Royal South Carolina, from late 1729 to the summer of 1739, was a period of great political, economic, and cultural progress. The increased attention from the Crown government inspired a generally optimistic sense of stability and security. We were at peace with our Spanish, French, and Native American neighbors, and the future looked bright. During this decade, the business of importing African captives increased dramatically in an attempt to keep pace with the expansion of South Carolina's plantation economy. Some members of the white minority felt uneasy about the volume of new Africans arriving through the port of Charleston, and some feared our Spanish neighbors were actively encouraging the enslaved majority to rise up against their masters. Both of these fears became a reality in September 1739, when a number of enslaved people living near the Stono River, in what is now the southern part of Charleston County, rose up against their white owners in a brief but bloody rebellion.

The first decade of Royal South Carolina, from late 1729 to the summer of 1739, was a period of great political, economic, and cultural progress. The increased attention from the Crown government inspired a generally optimistic sense of stability and security. We were at peace with our Spanish, French, and Native American neighbors, and the future looked bright. During this decade, the business of importing African captives increased dramatically in an attempt to keep pace with the expansion of South Carolina's plantation economy. Some members of the white minority felt uneasy about the volume of new Africans arriving through the port of Charleston, and some feared our Spanish neighbors were actively encouraging the enslaved majority to rise up against their masters. Both of these fears became a reality in September 1739, when a number of enslaved people living near the Stono River, in what is now the southern part of Charleston County, rose up against their white owners in a brief but bloody rebellion.

In the wake of the Stono Rebellion, two factors succeeded in drastically reducing the slave trade to South Carolina during the 1740s. First, the South Carolina legislature ratified an act on 5 April 1740 that was intended to curb the importation of further Africans. This temporary law imposed a prohibitively-high tax on arriving Africans through April 1745. Second, the ongoing war between Britain, Spain, and France, commonly called the War of Jenkins' Ear (1739–48), created serious disruptions to South Carolina's maritime traffic and effectively stopped the African trade. As a result of these two factors, only a very small number of Africans arrived in Charleston between 1740 and 1749.

In the second half of 1749, the flow of African slaves into Charleston recommenced with gusto. Throughout the 1750s and into the early 1760s, the enslaved population of South Carolina grew so rapidly that once again the legislature thought it necessary to intervene. Accordingly, on 25 August 1764, the South Carolina General Assembly ratified another temporary law imposing a prohibitively-high tax on newly-imported Africans. The tax had the desired effect; between November 1765 and February 1769, no new Africans legally arrived at the port of Charleston.

When the legal importation of African captives into South Carolina re-commenced in the spring of 1769, the merchants involved in this trade set to work with unprecedented vigor. The rate of slave-ship arrivals, and the raw numbers of Africans brought to Charleston in the early 1770s, far surpassed anything this port had ever witnessed. The clouds of war soon appeared on the horizon, however, and South Carolina's voracious appetite for fresh African captives was again threatened with disruption.

In the autumn of 1774, South Carolina sent delegates to a Continental Congress in Philadelphia to discuss how the American colonies could coordinate their response to British oppression. By mutual agreement with our American brothers-in-arms, on October 20th, the collected delegates adopted a set of fourteen articles, known as the Continental Association, that pledged colonial solidarity. Article 2 stated "We will neither import nor purchase, any slave imported after the first day of December next; after which time, we will wholly discontinue the slave trade, and will neither be concerned in it ourselves, nor will we hire our vessels, nor sell our commodities or manufactures to those who are concerned in it." Accordingly, after December 1st, 1774, no new Africans legally entered the port of Charleston, or any other American port, for the duration of what became our War for Independence.

The American Revolution ended in the spring of 1783, when the British Parliament and the fledgling United States government signed peace treaties and then exchanged ratified copies across the Atlantic Ocean. The end of war meant the end of the Congressional ban on the trans-Atlantic slave trade, but few Americans expressed an appetite for that unsavory business. After a decade of passionate rhetoric about freedom, liberty, and unalienable human rights, many Americans, especially those in the Northern states, sought to distance themselves from the practice of slavery. At the same time, however, a number of eager capitalists were quickly outfitting vessels bound for Africa. Here in South Carolina, the first cargos of "new Negroes," as they were called, began to arrive in Charleston harbor in the late summer of 1783.

Despite the return of peace in 1783, the American economy struggled to rebound after eight years of war. The newly-incorporated port city of Charleston was especially hard-hit, as was the Lowcountry of South Carolina in general. The import-export business was a major part of the economic fabric, but it took years to repair wartime damages and to negotiate the repayment of long-standing debts. After a brief period of rapid expansion and speculation, South Carolina's economy seemed to be on the precipice of a great crash. To prevent economic ruin, the state legislature felt compelled to intervene. On March 28th, 1787, our General Assembly ratified "An Act to regulate the recovery and payment of debts; and prohibiting the importation of negroes for the time herein mentioned." The ninth section of this law specifies that "no negro or other slaves, shall be imported or brought into this State, either by land or water, within three years from immediately after the passing of this Act." That is to say, no African slaves, newly imported or American born, were allowed to enter South Carolina from overseas or from neighboring states before 28 March 1790.

Less than two months after South Carolina passed a ban on importing African captives, delegates from each of the thirteen United States gathered in Philadelphia in the late spring of 1787 to debate the formation of a "more perfect union." During that Constitutional Convention, which lasted from late May through mid-September, several delegates from Northern states argued in favor of inserting language into the nation's charter to prohibit the growth of the institution of slavery. Ten states had already banned the importation of African captives. Men such as Luther Martin of Maryland argued that slavery was "inconsistent with the principles of the Revolution," and had no place in modern America. Delegates from three Southern states, principally those from South Carolina, argued to the contrary. Charles Pinckney, for example, bristled at the very notion of curbing the right of American planters to hold slaves. "If slavery be wrong," he told Congress, "it is justified by the example of all the world." John Rutledge, a former South Carolina governor, spoke for both Carolinas and Georgia when he flatly told Congress that the Southern states would not sign the Constitution without a clause protecting the slave trade.

In order to preserve the union of states, the delegates sought a compromise. A committee proposed to insert a clause into the Constitution pledging that Congress would not interfere with the trans-Atlantic slave trade before the year 1800. The South Carolina delegates rejected this offer. The committee then proposed a clause pledging that Congress would not interfere with the trans-Atlantic slave trade before the year 1808. After some discussion, the delegates from South Carolina and their Southern neighbors accepted this offer. Another compromise was to omit any direct references to slavery or slaves in the document, so as not to offend those who found the institution repugnant. Accordingly, the text of our United States Constitution, Article One, Section 9, includes the following curious clause: "The migration or importation of such persons as any of the states now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the year one thousand eight hundred and eight."

The text of the Constitution was completed in Philadelphia in September 1787, and then debated in each of the thirteen states. South Carolina's own Constitutional Ratification Convention met in Charleston in the spring of 1788 and approved the document on May 23rd. By September of 1788, eleven state conventions had ratified the Constitution, and so the document went into force. From that moment, the clock began ticking. It would be twenty years before Congress had the power to prohibit the importation of African captives. Proponents of slavery saw this timeframe as a Constitutional victory—a window of opportunity, if you will—but to some it was an absurd piece of irony.

South Carolina's own legislative assembly had voluntarily banned the importation of Negro slaves in March 1787 in order to check a post-war economic depression. So, while the U.S. Constitution, which went into effect in the autumn of 1788, permitted the resumption of that business, South Carolina remained committed to abstaining from the trans-Atlantic slave trade. In fact, on 4 November 1788, the South Carolina legislature ratified a new law that repealed the 1787 prohibition and imposed a fresh one. The preamble to the new "Act to Regulate the Payment and Recovery of Debts; and to prohibit the importation of Negroes for the time therein limited," states that the earlier law was found to be "inadequate to the relief of the distresses of the people of this State." After restructuring the policies concerning debt collection, the 1788 law further specified that "no negro or other slave shall be imported or brought into this State, either by land or water, on or before the first day of January, 1793." Through a series of six bi-annual legislative continuations, this prohibitive law remained in effect in South Carolina for a further fifteen years, through December 1803.

South Carolina's own legislative assembly had voluntarily banned the importation of Negro slaves in March 1787 in order to check a post-war economic depression. So, while the U.S. Constitution, which went into effect in the autumn of 1788, permitted the resumption of that business, South Carolina remained committed to abstaining from the trans-Atlantic slave trade. In fact, on 4 November 1788, the South Carolina legislature ratified a new law that repealed the 1787 prohibition and imposed a fresh one. The preamble to the new "Act to Regulate the Payment and Recovery of Debts; and to prohibit the importation of Negroes for the time therein limited," states that the earlier law was found to be "inadequate to the relief of the distresses of the people of this State." After restructuring the policies concerning debt collection, the 1788 law further specified that "no negro or other slave shall be imported or brought into this State, either by land or water, on or before the first day of January, 1793." Through a series of six bi-annual legislative continuations, this prohibitive law remained in effect in South Carolina for a further fifteen years, through December 1803.

During the 1790s, while South Carolina was not legally involved in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, there were two noteworthy national developments in this terrible business. First, our southern neighbors, North Carolina and Georgia, were actively taking advantage of their Constitutional right to import Africans (albeit in relatively low numbers). Second, the U.S. Congress passed a law on 22 March 1794 "to prohibit the carrying on the Slave Trade from the United States to any foreign place or country." Although this law was updated and strengthened by another Federal act ratified on 2 May 1800, it was of little consequence to the matter under consideration. This Federal law banned Americans from contributing to the growth of slavery in other places, but it was powerless to prevent the Carolinas and Georgia from exercising their Constitutional right to import slaves for their own use. In the end, however, it was a rather moot point. The North Carolina legislature voluntarily banned the importation of African captives in 1794, and Georgia followed suit in early 1798.

At the close of the eighteenth century, not one state in our Federal union was sanctioning the importation of African captives. If this situation had continued, the institution of slavery might have died a slow and natural death in the United States. Circumstances arose, however, that induced men in the plantation business to reconsider the potential value of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. First, the perfection of the cotton gin in the early 1790s and the rapid spread of that technology transformed cotton from a labor-intensive, unprofitable crop into very profitable international commodity. Then, in the spring of 1798, the U.S. acquired the Mississippi Territory, which included part of modern Alabama, thereby opening up millions of acres of potential cotton fields. Finally, in the spring of 1803, the U.S. purchased the vast Louisiana Territory, an act that signaled America's "manifest destiny" to expand to the shores of the Pacific Ocean. The combined effect of these three developments inspired thousands of agricultural men to head west and plant cotton. The new westward plantations would require labor, of course, but that commodity was in short supply. What could be done? On December 17th, 1803, after a nearly sixteen-year hiatus, the South Carolina legislature voted to resume immediately the importation of African captives.

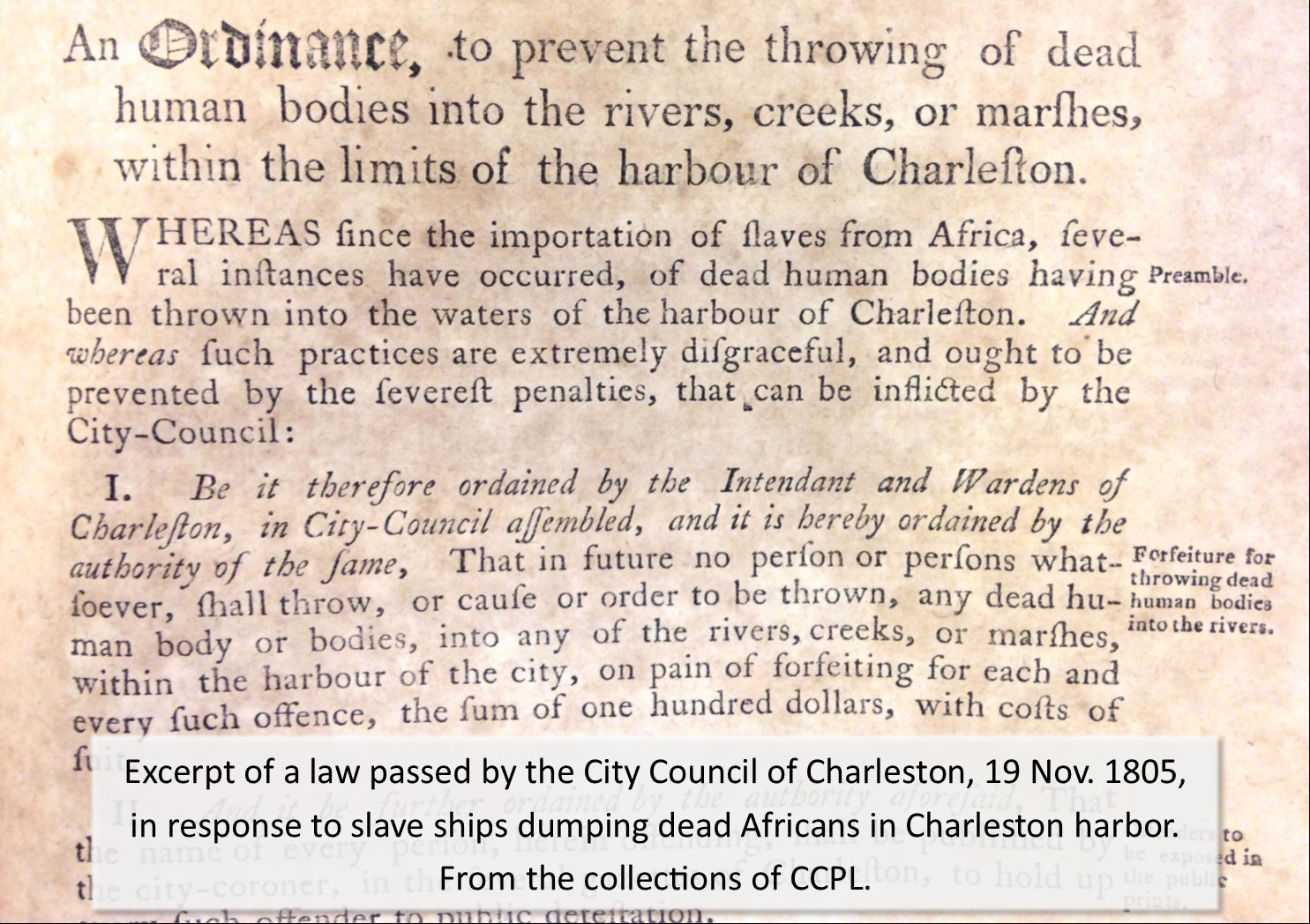

Starting in late December 1803 and continuing through the next four years, the port of Charleston witnessed a mad scramble to import as many Africans as possible before government intervened again. Everyone knew that the Constitutional compromise of 1787 had tied Federal hands from interfering with the trans-Atlantic slave trade before 1808, but the clock was ticking. For the merchants who financed the voyages and outfitted the ships, and the planters who paid top dollar for "new Negroes," it was nothing short of a feeding frenzy. During this last episode in the long history of importing slaves into Charleston, the rate of arrivals into Charleston, the number of bodies packed into each ship, and the callous exploitation of the human cargo exceeded the horrors of all previous years.

Starting in late December 1803 and continuing through the next four years, the port of Charleston witnessed a mad scramble to import as many Africans as possible before government intervened again. Everyone knew that the Constitutional compromise of 1787 had tied Federal hands from interfering with the trans-Atlantic slave trade before 1808, but the clock was ticking. For the merchants who financed the voyages and outfitted the ships, and the planters who paid top dollar for "new Negroes," it was nothing short of a feeding frenzy. During this last episode in the long history of importing slaves into Charleston, the rate of arrivals into Charleston, the number of bodies packed into each ship, and the callous exploitation of the human cargo exceeded the horrors of all previous years.

Meanwhile, newspapers throughout the Northern states roundly condemned South Carolina for reverting to such savage behavior. In our nation's capital, the vast majority of Federal representatives were determined to close the trans-Atlantic slave trade as soon as possible. The Constitution specified that Congress could make no law regarding slavery prior to the year 1808, but the political majority was getting impatient. Accordingly, on March 2nd, 1807, the U.S. Congress ratified "An Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves." This pre-emptive law simply states that the importation of any person for the purposes of slavery shall become illegal on the first day of January, 1808, and thereafter, it shall be illegal for any U.S. citizen to participate, in any way, in the transportation of any people for the purposes of slavery.

When the first day of January 1808 finally arrived, the port of Charleston dutifully obeyed the new Federal law and banned the arrival of any further slave ships from Africa. The people of Charleston had witnessed a mad dash to the beat the deadline, and the dust slowly settled down in the spring of 1808. The "final victims" of Charleston's voracious appetite for slaves arrived in December 1807, but several thousand were not sold until the middle of 1808. In an effort to squeeze every bit of potential profit out of this nefarious business, some merchants held their final stock of "new Negroes" for months after the arrival of the new year, hoping to drive prices higher and higher. By the end of 1808, however, the sales were over and almost all of newly-enslaved people had moved westward. Charleston's central role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade was now a thing of the past.

The traffic of importing Africans through the port of Charleston officially ended in January 1808, after 137 years of turbulent activity, but the practice of slavery continued in our community until late February, 1865. Some African captives were undoubtedly smuggled onto our shores during the first half of the nineteenth-century, but such events represent isolated aberrations from the law that are nearly impossible to document. For the purposes of today's discussion, I've consciously focused on the legal framework of the trans-Atlantic slave trade in South Carolina. This material provides a very important and very necessary framework for developing a broader conversation about quantifying and narrating the story of the nearly 200,000 African people who entered this country in bondage through the port of Charleston. I believe this is a massively important conversation for the spiritual health of our community, our state, and our nation. It's not the most pleasant topic of conversation, but it's one that I hope you'll agree is very necessary.

PREVIOUS:Charleston's First Ice Age

NEXT: The Story of Gadsden's Wharf

See more from Charleston Time Machine

farrellthatimbers.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/end-trans-atlantic-slave-trade

0 Response to "The Slave Trade Would Continue for 20 More Years"

Postar um comentário